It started like any other Saturday in Ghana. The usual banter in trotros, the early risers poaching for their specific commodities and services, traders busy with their exchange, And then came the news. Softly at first, like a whisper behind the ears, “Daddy Lumba has passed.”

Just like that, the man who gave Ghana some of its most unforgettable anthems had danced his last dance. No farewell concert. No cryptic goodbye. No final verse. Just a pause. A heart-wrenching, teary-eyed pause. The kind that turns your bones cold and your memories warm.

For many, it didn’t make sense. How could the man whose voice raised generations go so quietly into the night? How could someone who gave us over 30 albums, shaped entire genres, and stood the test of time become a headline we all wished was false?

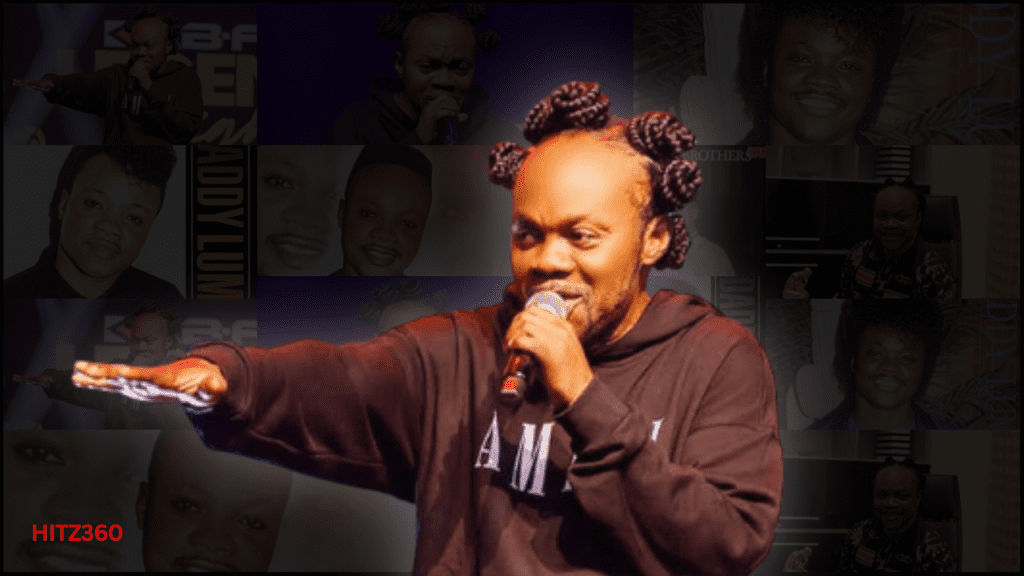

But it was true. It is true. Charles Kwadwo Fosu, known and loved as Daddy Lumba, had bowed out of life’s stage on Saturday, July 26, 2025, at the Bank Hospital in Cantonments. At just 60 years old.

His death came like a thief in the night—but left behind a trail of candles, voices, and tears. From old women clutching rosaries to young men with Lumba’s lyrics tattooed on their skin, Ghana was in mourning. Radio DJs paused in mid-sentence. News anchors lost their composure.

People who thought they had no more tears left for celebrities found themselves weeping as if they had lost a father. Because that’s what Daddy Lumba was, he was their Father. To the broken-hearted, he was a mirror. To the proud, he was a hymn. To the hopeful, he was a rhythm, and to Ghana, he was a national treasure wrapped in mystery.

Roots in Nsuta – Daddy Lumba Before the Music

Before his name rolled off the tongues of millions, Charles Kwadwo Fosu was simply a boy. A boy whose footprints were first traced in the dusty paths of Nsuta Amangoase, a modest town tucked into the green folds of the Ashanti Region of Ghana. And if you’ve ever been to Nsuta, you know it’s a place where voices carry far and hearts carry heavy. It’s the kind of town where people know your grandfather’s story better than you do, and where silence is often more telling than sound.

Charles was born on September 29, 1964, a child of both promise and paradox. He came into the world not with thunder or fanfare, but with a quiet spirit that people remembered.

His mother, Comfort Gyamfi, known throughout the town as Maame Comfort or Ama Saah, was the kind of woman who made sacrifices without announcing them. She raised her children with grit tucked neatly beneath her wrapper. A devout Christian with the voice of an angel and the strength of a lioness, she didn’t just cook and clean, she carved out dreams for her children in a world that often closed its doors to the poor.

Charles’ father, Kwadwo Fosu, was there, but not always. A man of few words and even fewer appearances, his presence in young Charles’ life was more shadow than substance. Some say he was a rolling stone, a man chasing dreams of his own. Others say he simply wasn’t ready for a child who would one day carry the weight of a nation’s heart on his voice. Whatever the truth was, Maame Comfort bore the burden alone with grace, with tears, and with a lot of prayer.

Charles grew up in a household where music was not taught in formal lessons—it was lived. The melodies of life played through every moment: the clanging of the kitchen pots, the rhythmic sweeping of the compound, the echoing calls to prayer from nearby churches. Sundays were sacred not just because of church, but because of the songs. Gospel music seeped into his bones like rain into dry earth.

He didn’t just enjoy the music, he dissected it. Even as a child, Charles had a habit of quietly studying things. He’d stare at people mid-conversation, watching the way their voices rose and fell. He was different, and everyone knew it.

When Charles finally stepped into senior high school education at Juaben Secondary School, he didn’t walk in as a boy looking for grades. He walked in as a soul already searching for a sound.

Juaben was no ordinary school. It was a place of ambition, a crucible where future leaders and industry players were quietly forged. And while many students crammed textbooks and chased exam scores, Charles was chasing something else: resonance.

It was here that he started writing. Not essays. Not speeches. But lyrics. Thoughts that danced between rhyme and rhythm. He’d scribble lines in the margins of notebooks, use break time to rehearse melodies, and hum to himself as if the corridors were his concert hall.

And then came the magic: the formation of a small group that would later become the original Lumba Brothers. These were not professional musicians. They were boys with dreams larger than their means. But in their harmonies, there was a fire. A spark. A kind of hope you could almost touch.

The group sang at school events, local functions, and wherever they could find a microphone or even a table to drum on. Charles quickly became the front man, not because he forced his way to the center, but because the center naturally belonged to him. His voice had weight and his presence had mystery.

One former classmate once said, “When Charles sang, it felt like your soul had been seen. Not heard. Seen.” That was the beginning of what would become one of Ghana’s greatest gifts to the world. But school couldn’t hold his spirit forever. And neither could Nsuta. Dreams that big always outgrow small towns.

The First Mentors and the Silent Training

There’s a saying in Akan: “Sɛ wo werɛ fi na wo san kɔfa a, yɛnkyiri.” which translates as, If you forget and return to pick it up, it is not wrong. Charles never forgot where he came from, but his wings were ready to spread.

Long before any record deal, long before he stood next to presidents and played to sold-out crowds, Charles had already trained himself. He had no formal music education, not in the Western sense. But he had ears like a hawk and a memory like a sponge.

He learned by listening. He studied the pauses between guitar notes. He mimicked the breathing patterns of other musicians phrasing. He’d sing gospel and slow it down to feel the pain in it.

But most of all, he watched people. He understood human emotion better than most. That was his real training. If someone was betrayed, he could write a song about it. If someone was in love, he could sing exactly how they felt. It wasn’t just music. It was emotional therapy with a melody. People say talent is God-given. But what Charles did with his was sacred.

Education and the First Band – The Echo Before the Storm

Teachers said he had the focus of an old man trapped in a young body. Classmates called him “the quiet one.” He didn’t speak much, but when he did, his voice had depth. He carried himself like someone who had seen the future and knew he belonged in it. And while others filled their free time with arguments over football or chasing girls across the courtyard, Charles was listening. Always listening.

Whiles Charles was in secondary school, bands were the thing of that era with over 60 successful music bands touring the country. It was during these school years that he began forming what would later become the first incarnation of the Lumba Brothers. Not the record-breaking duo you know with Nana Acheampong, no not yet. This was the raw version. The humble beginning, born from borrowed instruments and second-hand microphones, fueled by nothing more than grit and a love for sound.

They weren’t performing for fame. There was no internet, no social media, no awards to chase. They performed because the music inside them would not be quiet. When they sang at school events, you could feel the room change. It was more than entertainment, it was spiritual. It was prophetic.

Charles never attended any conservatory or music academy. But what he got from life was worth more than any formal training.

His first teachers were the market women singing while going about their business, the church deacons harmonizing hymns, the sound of a palmwine guitar drifting through the dusk.

He studied the timing of highlife, the melancholy of Ghanaian gospel, the cheeky rebellion of palmwine music. And through it all, he began to develop his own voice, a sound that was familiar, yet hauntingly new.

He loved the smooth stylings of Nana Ampadu, the raw soul of E.K. Nyame, and the storytelling of Agya Koo Nimo. He was especially fascinated by the way these legends wrapped life’s hardest truths in sweet melodies. Pain disguised as poetry. Heartbreak hidden in harmony. That would later become Lumba’s trademark.

One of his mentors during this time was an elderly choirmaster known only as Uncle Paa Joe, a retired church musician who took Charles under his wing. It was Paa Joe who taught him the importance of control, cadence, and emotion. “Don’t just sing notes, Charles,” he would say, “sing meaning.”

And so he did. Over and over. Late into the night when others were asleep, Charles was writing. Practicing. Rehearsing conversations he’d never had. His schoolbooks became lyric pads. His lunch table became a drum kit. Every moment was music. It was never just a hobby. It was a calling. He was being prepared, not promoted.

To understand Daddy Lumba’s rise, you need to understand the Ghana he was growing up in. The late 1970s and early 1980s were not gentle years.

The economy was biting. Military regimes came and went like rainy seasons. Power outages were frequent. Food prices soared. Hope was shrinking. Ghana was surviving, but only just.

And yet, amidst the chaos, music remained one of the few things Ghanaians could hold onto. It was both protest and prayer. Young Charles saw this. He watched how a single song could change a mood, inspire a crowd, or heal a broken heart. He began to understand that music was power and not just to entertain, but to awaken and unite.

And somewhere in the small town of Juaben, a quiet student began to think: “If these legends could do it, why not me?”

But Ghana had its limits. For a young man with vision like Charles, the walls were closing in. After finishing secondary school, he faced the hard reality most dreamers face which was how to feed a dream when the kitchen is empty.

He had no industry connections. No rich uncle. No powerful godfather. All he had were songs and faith. So he made the choice many young Ghanaians made in those years. He left.

With barely enough money to keep him warm, Charles boarded a flight to Germany, not in search of fame, but survival. He wasn’t going there to become Daddy Lumba. He was going there to stay alive.

Hard Roads and Heavy Dreams: Ghana to Germany

Every journey to greatness begins with a step away from comfort. For Charles Kwadwo Fosu, that step took him from the familiar dust of Nsuta to the cold pavements of Germany, a land that didn’t know him, didn’t expect him, and certainly wasn’t ready for him.

He left Ghana with a suitcase full of prayers and a heart full of hope. But life abroad was not the postcard dream. Germany welcomed him with harsh weather, harder language, and the cold shoulder of immigration reality. He was just another Black man trying to make ends meet in a world that barely saw him as human, let alone as a future icon.

There was no red carpet waiting. There were no fans or fancy microphones. Just odd jobs, isolation, and a sense of not belonging.

He cleaned hotel rooms. He worked in restaurants. He lifted boxes in warehouses. Every euro earned was soaked in sweat. But even in those dark moments, he never let go of the music. It followed him to work. It hummed through the cold. It clung to his spirit like a second skin.

Then, by what some would call coincidence but others would call divine arrangement, he met Nana Acheampong again. His old schoolmate from Juaben, who also had melodies dancing in his soul.

The spark was instant. Two boys from Ghana, stuck in a foreign land, bonded by rhythm and survival. It was more than friendship. It was fate tuning its instruments.

Together, they decided to form a band: the Lumba Brothers, resurrecting the name from their secondary school days, but this time with fire in their eyes and music that begged to be heard.

They wrote in their tiny apartments, recorded rough demos with cheap equipment, and hunted studios like hungry wolves. They were nobodies in Germany, but in their minds, they were already stars back home.

After years of sacrifice and scraping coins together, they released their first official album in 1989:

“Yɛɛyɛ Aka Akwantuo Mu” (We Are Suffering Abroad)

It was more than music. It was a letter to every Ghanaian struggling outside the country. A soundtrack of survival. A voice for the voiceless and yes it blew up.

Back in Ghana, the cassette spread like wildfire. Taxi drivers played it on loop. Market women sang it while selling tomatoes. Even pastors nodded to its message. The Lumba Brothers had struck gold and not in euros, but in hearts. Germany may not have clapped, but Ghana danced.

The Birth of the Lumba Brothers Sound

“Yɛɛyɛ Aka Akwantuo Mu” wasn’t just a hit, it was a movement. The album captured a moment in Ghana’s history when the youth were leaving in droves, searching for better lives across Europe and America. The lyrics weren’t just words; they were truth wrapped in sorrow, and wrapped again in melody.

With that album, the Lumba Brothers carved a new path in Ghanaian highlife as they dared to be different. Nana Acheampong, with his smooth voice and romantic delivery, became the perfect duet partner. Daddy Lumba brought depth, unpredictability, and spiritual charge to their music. Their chemistry was like black and white keys on a piano, opposite but perfect together.

They followed up with more albums and performances, gradually becoming household names across Ghana and in the diaspora. But as with many great duos in music history, individual callings eventually pulled them apart. Not out of bitterness, but out of growth.

Going Solo – The Breaking of the Mold

In the early ’90s, Lumba made a move that many feared, he went solo. And at first, critics whispered. “He won’t survive without Nana Acheampong.” “They were better as a pair.” But Daddy Lumba wasn’t trying to survive, he was trying to transform.

His first solo project, “Obi Ate Me So Bo”, was like a slap in the face to every doubter. It wasn’t just a success, it was a revolution. The Lumba the nation met in this album was no longer the sweet harmonizer of old. He had evolved into something bolder, darker, deeper.

Gone were the clean-cut images. In came the suggestive lyrics, the emotional confessions, the spiritual undertones, the playboy themes, and the vocal unpredictability that became his signature. Daddy Lumba had become a mirror for Ghana’s complexities which was love, pain, deceit, spirituality, betrayal—all poured into highlife beats that now felt both familiar and brand new.

And Ghanaians? They ate it up like Sunday jollof. Over the next few years, he released a cascade of albums:

Playboy, Theresa, Aben Wo Ha, Ebi Se 3nni, Sika Asɛm. Each one layered in truth, sin, wit, and grace. Each one revealing a different sides of Lumba from the lover, the prophet, the rebel, and to the preacher. He wasn’t just releasing music. He was building a legacy one song at a time.

Daddy Lumba – The Musician, The Prophet, The Enigma

Some musicians make songs. Others make waves. But Daddy Lumba? He made statements. He wasn’t just a singer. He was a puzzle wrapped in a melody—a riddle only the soul could decode. The moment his voice hit a speaker, you didn’t just listen—you paused. Doesn’t really matter who you’re are Lumba’s songs cut through the layers and landed straight in your chest.

But what made his music so… haunting? Let’s start with his lyrics. Lumba didn’t spoon-feed you meaning. No. He’d lace a track with Akan proverbs, flip the direction midway, and leave your ears arguing with your heart. A song would begin like a love ballad, but by the third verse, he was talking about betrayal, politics, or death. He’d whisper to you about romance, and just when your guard dropped, he’d throw in a line that made your grandma cross herself in confusion.

Take “Aben Wo Ha”, for instance.

A song so controversial that some radio stations were afraid to play it at first. Why? Because it flirted. It teased. It dared. But even though it raised eyebrows, it also raised the roof, becoming one of the most played songs in Ghanaian history.

And then there’s “Theresa” a song so tender, so personal, it feels like he tore a page from his private diary and handed it to the world.

Every Lumba song carried double meanings.

Was “Sika Asem” about money ruining love or was it a warning to politicians and fake pastors?

Was “Menya Mpo” a song about disappointment or was he talking about the music industry?

You never really knew. And that was the magic.

Daddy Lumba was a walking paradox. The long, silky permed hair. The designer clothes. The sunglasses—indoors or outdoors. He looked like a rockstar from the Caribbean, yet sang like your Ashanti uncle. People mocked his style until they realized he had made it his armor, a shield against expectations and a brand so unique, you couldn’t copy it without being laughed at.

Mentor & Gatekeeper – Those He Brought Up

Behind every great king is a generation he lifts. Daddy Lumba wasn’t just a solo star—he was a launchpad for others. Many of Ghana’s household names didn’t walk into the industry by luck. They walked in holding Lumba’s hand.

Let’s talk about Ofori Amponsah, the crooner who many believed was a Lumba duplicate. Their collaboration album “Wo Ho Kyere” was more than a project as it was an initiation. Ofori was young, raw, and unsure. But under Lumba’s wing, he blossomed.

Together, they created some of the most soulful love songs of the early 2000s, blending spiritual undertones with bedroom whispers. And when the time was right, Lumba let him fly solo. He didn’t gatekeep. He released him into greatness.

Then there’s Felix Owusu, another powerful voice shaped in Lumba’s studio space. Not to mention Borax, Great Ampong, and even the controversial gospel collaborations that made headlines across churches.

But mentoring for Lumba wasn’t just about music. It was about spirit. Discipline. Sound control. Performance. The business of royalties. The art of staying relevant. He gave them more than a stage. He gave them a compass.

Some couldn’t keep up. Some drifted. Some, sadly, him. But that’s the price of leadership. Still, he never stopped supporting the younger generation. Even into his later years, he recorded songs with fresh acts, inspired covers of his old hits, and appeared at surprise shows to remind everyone that legacy isn’t just what you leave behind, it’s who you bring along.

The Private Man – Family, Spirituality, and Mystery

You could write 100 books about his music and still miss the man himself. Because Daddy Lumba was, above all, a master of mystery.

He was everywhere, yet you rarely saw him in interviews. He was loved by millions, yet very few truly knew him. He’d be on stage in Takoradi one night, then vanish from the public for a year. And in his absence, rumours would rise like vapour in harmattan. But that was by design.

He kept his family life behind a curtain of respect. His wife, children, siblings as they rarely surfaced in the spotlight. In a world that devours celebrity privacy like kelewele on a rainy night, Lumba drew a line and stood behind it.

Then there was Maame Comfort, his beloved mother, whose influence on his career was not just emotional, but spiritual. He sang about her, cried for her, and in many ways, lived in her shadow. When she passed, Lumba changed.

The man who once wore gold rings and laughed through controversial verses suddenly grew quiet. More songs about heaven. More references to judgment day. Albums like “Hosanna” hinted at a man wrestling with mortality, with regrets, with the future beyond this world.

Some say he became more spiritual. Others say he became reclusive. Truth is, he was always both. He could flirt with the world on track 1, and then beg God for mercy on track 10. That was his balance. His burden. His brilliance. He lived as though life was one long album with some parts loud, some parts soft, but always intentional.

Legacy, Death, and the Final Goodbye

Some people walk through life. Others glide.

But Daddy Lumba? He moonwalked through time effortlessly defying every rule, every trend, and every doubt.

From the humble corners of Nsuta to global stages and million-album sales, Daddy Lumba didn’t just live a musical life, he authored a new gospel of artistry in Ghana. A gospel where music was both celebration and confession. Where songs were not merely for dancing, but for decoding.

His musical legacy is etched in every speaker that ever blasted “Adaka Teaa” at a funeral. It lives in every couple who danced to “sumyɛ kasa a” at their wedding. It breathes in the background of trotro rides, Saturday morning clean-ups, and might life.

He redefined highlife, not by rejecting its roots, but by fertilizing them with raw truth, modern flair, and spiritual spice. From romantic pain to social critique, from spiritual introspection to downright flirtation, his discography reads like the diary of the Ghanaian soul.

He released over 30 albums, created over 200 original songs, and mentored a lineage of musicians who still carry pieces of his sound in their voices. Artists like Ofori Amponsah, Great Ampong, and even newer highlife singers owe their sonic DNA to Lumba’s blueprint.

And then… he left. Silently. Suddenly. There was no dramatic press conference. No farewell tour. Just… silence. The kind of silence that screams louder than thunder.

When the news broke, it didn’t just hit the entertainment scene. It shook the spine of the nation. From Accra to Kumasi to Tamale, from Tepa to Goaso to Takoradi, hearts sank. Radios switched to full Lumba playlists. Old men cried like children. Women clutched their wrappers. Young artists, who never met him but worshipped his sound, and tributes poured with trembling hands.

And in that grief, a realization washed over everyone like a wave: We hadn’t just lost a musician. We had lost an identity, A cultural compass, A rare spirit.

His death feels like a chapter ending before we turned the page. But perhaps, that’s how giants leave. They don’t warn you. They just disappear, and all you’re left with is their echo.

And as he quoted in his Adaka Teaa song

“ Yɛn nyinaa yɛde owuo ka” ( we all owe death), we shall join him too…

The Echo After the Song

Long after the candle is blown out, the smoke still rises. Long after the curtain falls, the stage still echoes with footsteps. And long after Daddy Lumba’s voice is silenced, his music plays on.

But what does he truly leave behind?

Not just awards. Not just platinum records or packed concerts. He leaves behind a spiritual archive. A record of Ghanaian emotion, stitched into sound. He gave us permission to cry, to laugh, to flirt, to repent, to boast, to reflect—and sometimes, to do all that in one track.

He taught us that vulnerability wasn’t weakness. That you could wear heartbreak like a medal. That you could worship on one track and question God on the next. That you didn’t have to be perfect to be powerful.

In his life, he bore scars that never made headlines. He fought health battles privately. He endured betrayal, loneliness, and the crushing weight of fame. But through it all, he kept creating.

He never stopped singing.

When that final casket is lowered, when the dust swallows his physical frame, what will remain is not just a name on a tombstone. What remains is an institution, A cultural monument, A melody stitched into the Ghanaian DNA.

Let us remember him not just as a singer, but as a symbol of survival. A young man who left Ghana with hope in his pocket and returned with music in his hands. A boy from Nsuta who became a voice for the voiceless, a lover for the broken, a spiritual vessel for the tired.

And so now, as we stand at the edge of this long, painful farewell, we must do one thing:

Play the music, Let the guitars cry, Let the drums testify. Let the old records spin until the neighbors complain. Because the man may be gone, But the music? The music is immortal.